Octopus Totem

Mētis Musings

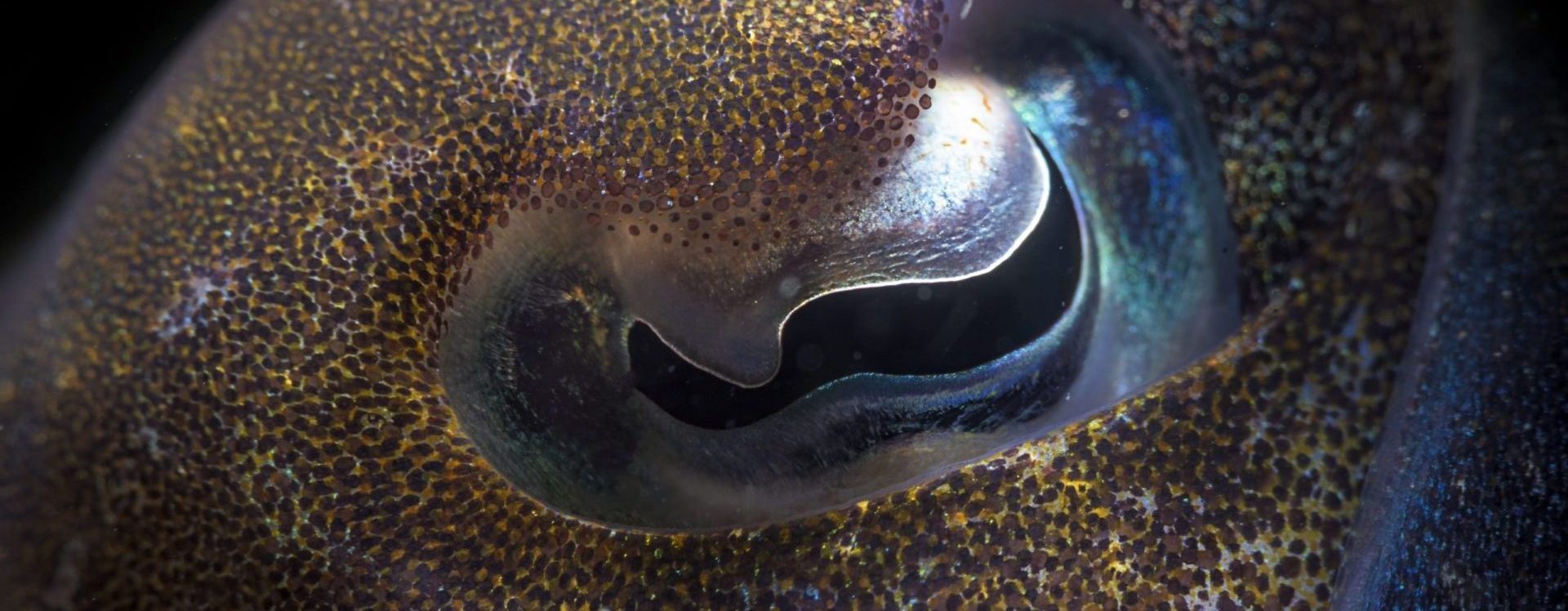

Octopus as Totem: A Mētis Metaphor

Mētis intelligence often shelters inside the contemporary language of instinct, intuition, and gut-wisdom, taken for granted and at times misattributed to other human activities. But the Greeks honored mētis and wanted to see it cultivated in its youth. leaders, and society. Detienne and Vernant note how the Greeks particularly use animal-metaphor as a heuristic for the perplexed: Be like the fox, who plays dead only to snatch the animals coming to feast on carrion. Be like the seal, whose ambiguous and awkward appendages allow it to navigate both land and sea. Be like the sea bird who soars on the winds and finds the only safe path through the dark storm. Be like the horse, whose daimonic nature cooperates with bit and bridle only by consent, with no dampening of its inner fire. Be like the fish whose eyes never close and who angle for the little fishes through a vigilant stillness. Be like the octopus, whose enigmatic flexibility and cleverness allows infinite adaptation and disguise. This interest in animal totems reminds of me of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra who exclaims of his companions, the eagle and the snake: “The proudest animal under the sun and the wisest animal under the sun – they have gone forth to scout. . . Let my animals guide me!” (1:10). Travelling under totem is also named in Nietzsche’s metamorphoses of spirit, from camel to lion to child. What other animals might be called forth for wisdom journeying?

Countless animals are endowed with mētis. Oppian describes at length the pranks of ichneumon, and the cunning tricks of the Ox-ray; he marvels at the metis of the starfish and the urchins and at the techné of the crab with its twisted gait. But of all the animals which are outstanding for their mētis , there are two which call for particular attention: the fox and the octopus. In Greek thought they serve as models. They are, as it were, the incarnation of cunning in the animal world. Each represents one essential aspect of mētis in particular. . . In the infinite suppleness of its tentacles the octopus, for its part, symbolises the unseizability that comes from poymorphy. (Detienne and Vernant, 34)

I want to particularly focus on the Greek interest in the octopus (and its cephalopod kin – the cuttlefish) as a metaphor for mētis, but first a quick note. Metaphors are truly a sound, not to mention accessible and imaginative, strategy for wisdom practice. As George Lakoff and Mark Johnson note in their influential work, Metaphors We Live By (1980) metaphor serves as “a mechanism for creating new meaning and new realities in our lives” (196).

New metaphors have the power to create a new reality. This can begin to happen when we start to comprehend our experience in terms of a metaphor, and it becomes a deeper reality when we begin to act in terms of it. If a new metaphor enters the conceptual system that we base our actions on, it will alter that conceptual system and the perceptions and actions that the system gives rise to. (Lakoff and Johnson, 145)

The reason we have focused so much on metaphor is that it unites reason and imagination. . . . Metaphor is one of our most important tools for trying to comprehend partially what cannot be comprehended totally: our feelings, aesthetic experiences, moral practices, and spiritual awareness. These endeavors of the imagination are not devoid of rationality; since they use metaphor, they employ an imaginative rationality. (ibid, 193)

In short, to play with metaphor is to engage our mētis and its power to sniff out our life’s meanings. So let us turn to an old metaphor and make it fresh for us again. The octopus is not a common totem for wisdom, but it is my new favorite for those “feelings, aesthetic experiences, moral practices, and spiritual awareness” that are the hallmarks of mētis wisdom and its creative becoming. I can see several aspects of the octopus (and cuttlefish) that are worth noting, and in sharp contrast to certain forms of human foolishness and vice, including showy ambition, posturing displays, inflexible strategizing, naïve bravado, fixed mindsets. I have pulled the following citations from Detienne and Vernant’s inspiring work, Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society (1978).

1. The wisdom of the octopus is patient and discerning for the just-right time, resisting any drive to move for movement’s sake. Cephalopods pass the “marshmallow test,” in which immediate gratification is set-aside for a surer or richer future.

The concentration and vigilance which the young man displays throughout the race resembles that of the octopus constantly lying in wait for its prey. . . directly involved in the difficulties of practical life with all its risks, confronted with the world of hostile forces which are disturbing because they are always changing and ambiguous. Mētis – intelligence which operates in the world of becoming, in circumstances of conflict – takes the form of an ability to deal with whatever comes up, drawing on certain intellectual qualities: forethought, perspicacity, quickness and acuteness of understanding, trickery, and even deceit. (43-44)

The ephēmoros one is an inconstant man who at every moment feels himself changing; he is aware of his state of flux and veers at the slightest puff of wind. The polútropos one, on the other hand, is distinguished by the control he possesses: supple and shifting as he is, he is always master of himself and is only unstable in appearance. . . not the plaything of movement but its master. (40)

2. The wisdom of the octopus is both modest and clever, sensitively adapting itself or hiding in plain sight with profound social intelligence and cunning intent.

The octopus is renowned for its mētis. . . . elusive: its mēchanē enables it to merge with the stone to which it clings. Not only is it able to take the shape of the bodies to which it clings perfects, but it can also imitate the colour of the creatures and things which it approaches. . . . Like the fox, the octopus defines a type of human behavior: “Present a different aspect of yourself to each of our friends . . . Follow the example of the octopus with its many coils which assumes the appearance of the stone to which it is going to cling. Attach yourself to one on one day and, another day, change colour. Cleverness (sophiē) is more valuable than inflexibility (atropiē).” (38-39, and citing Theogonis)

3. The wisdom of the octopus reverses direction or responds ambiguously when fitting, never shy to sidestep the direct or expected path. Like Hephaestus, its divergent appearances are a mark of its mētis.

These elusive, supple cephallopods which developed into a thousand agile limbs are enigmatic creatures. They have neither front nor rear, they swim sideways with their eyes in front and their mouth find, their heads haloed by their waving feet. . . They are oblique creatures the front of which is never distinctly distinguished from the rear, and in their being and in the way they move, they create a confusion of directions. (38)

4. The wisdom of the octopus creates its own inky shadows and darkness, misdirecting voyeurs and adversaries to protect both its paths and its privacy.

It is a liquid blacker than pitch, a kind of magic philtre, pharmakon, which can produce a dark cloud. When they emit this mist of night, “the black cloud of liquid disturbs the water all around and conceals the paths of the sea” at the same time making it impossible to see anything. In this way the cuttlefish find their own póros through the aporia they have created: “they swiftly escape along the path created by the tholos, diá tholóentos póroio.” In this text about the cuttlefish spreading its night deep down in the water, it is interesting to find Oppian using both meanings of the word póros: on the one hand to suggest a way of getting out of difficulties, the stratagem employed by a creature of guile endowed with mētis, and, on the other, to refer to a path, way through or crossing. (161)

Cuttlefish and octopuses are pure áporai in the impenetrable, pathless night that they secrete is the most perfect image of their mētis. Within this deep darkness, only the octopus and the cuttlefish can find their way, only they can discover a póros. The night is their lair. . . it is a night which it can itself secrete. (38)

5. The wisdom of the octopus is an embodied, many-armed intelligence for solving puzzles without being trapped by them.

While the fox is as supple and as slim as a lassoo, the octopus reaches out in all directions through its countless flexible and undulating limbs. To the Greeks, the octopus is a knot made up of a thousand arms, a living interlacing network, a polúplokos being. (37)

The polúplokos octopus is a knot composed of a thousand interweaving arms; every part of its body is a bond which can secure anything but which nothing can seize. . . it is a master of bonds. Nothing can bind it but it can secure anything. Bonds are the special weapons of mētis. To weave and to twist are key words in the terminology connected with it. (41)

What child (or adult for that matter) has not been entranced by the octopus who unscrews the jar and crawls inside? Add to that its other virtues and we have a totem that is more cunning than the lion or the bear, with a uniquely wily and creative nature. Life’s challenges often need more creativity than force, and this is the power of mētis. As I think back on the cultural metaphors that shaped my life to date, they have not been like the octopus. They have framed virtue as disclosive, steely, direct, conforming, cooperative, naïve, unambiguous, static, unyielding. Painful experience tells me how often these virtues are both taught and exploited by those with privilege and/or wicked cunning. Too often these metaphors in their rigid prescriptions were traps. Not so:

. . . the primordial deities of the sea whose mētis, as subtle and flexible as the coming-to-be over which they preside relates not to that which is straight and direct but to that which is sinuous, undulating and twisting; not the unchanging and fixed but to the mobile and everchanging; not to what is predetermined and unequivocal but to what is polymorphic and ambiguous. (Detienne and Vernant, 160)

The octopus as totem offers us fresh approaches to virtue with its own distinctive mētis. Under the octopus totem, I can watch and wait. I can hide. I can blend in. I can protect myself from exposure. I can be stealthy and silent. I can be a creature of ink and shadows. I can follow my own divergent or ambiguous path. I can honor the wisdoms of my body and its many-armed dimensions and powers. I can solve puzzles on my own terms without being entrapped. To point, my curiosity will not be given over to the fate of Pandora. Animal totems invite wisdom – prescriptive metaphors that can be both fresh and empowering. Be like the octopus.

One last note for the curious. Lakoff and Johnson (1980) and Detienne and Vernant (1978) all note the problematic dominance of Platonic privileging of Being, essentialism and Universal Truth at the expense of a Mētis Becoming through the subtle, shimmering, poetic, oblique, and metaphorical manifestations of wisdom.

Plato is at pains to give us a detailed description of the components of mētis in order to lend added weight to his reasons for condemning this form of intelligence. (Detienne and Vernant, 316)

It is already a counter-cultural octopus-maneuver – particularly for those of us immersed in cultures of unapologetic Platonism and its essentialist “Truths” – to play with metaphors for our defiant metamorphosis.

Objectivism and subjectivism need each other in order to exist. Each defines itself in opposition to the other and sees the other as the enemy. . . In Western culture as a whole, objectivism is by far the greater potentate, claiming to rule, at least nominally, the realms of science, law, government, journalism, morality, business, economics, and scholarship. . . Plato viewed poetry and rhetoric with suspicion and banned poetry from his utopian Republic because it gives no truth of its own, stirs up the emotions, and thereby blinds mankind to the real truth. Plato, typical of persuasive writers, stated his view that truth is absolute and art mere illusion by the use of a powerful rhetorical device, his Allegory of the Cave. To this day, his metaphors dominate Western philosophy, providing subtle and elegant expression for his view that truth is absolute. Aristotle, on the other hand, saw poetry as having a positive value: “It is a great thing, indeed, to make proper use of the poetic forms, . . . But the greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor” (Poetics 1459b); “ordinary words convey only what we know already; it is from metaphor that we can best get hold of something fresh” (Rhetoric 1410b). But although Aristotle’s theory of how metaphors work is the classic view, his praise of metaphor’s ability to induce insight was never carried over into modern philosophical thought. With the rise of empirical science as a model for truth, the suspicion of poetry and rhetoric became dominant in Western thought, with metaphor and other figurative devices becoming objects of scorn once again.” (Lakoff and Johnson 189-190)

Strikes me that one of the powers of all animal totems is that, in their freedoms, they are immune to scorn. Just one more reason to follow their lead towards fresh forms of virtue.

References

- Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant. Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society. Translated by Janet Lloyd. New Jersey: Humanities Press, 1978.

- Freidrich Nietzsche. Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Translated by Adrian Del Caro. Cambridge University Press: 2007.

- George Lakoff and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press: 1980.

Teacher

An experienced instructor, clinical supervisor and recipient of multiple teaching awards, inviting joy and insight in training and teaching settings.

Coach

A board-certified coach, specializing in executive and professional care for strength-building and creativity at growth edges and in leadership.

Speaker

An authentic and warm public speaker, weaving interdisciplinary insights and humanistic perspectives to support a deepening sense of community.

Demand meaning in the moments of your life.

Chart a navigation course that is clear-eyed and nimble.

Cultivate the habits of perspective, creativity, and curiosity.

Call forth your fiercest capacities for courageous authenticity.

Seek Wisdom.

Janēta Fong Tansey, MD PhD