Mētis Musings

Mētis and Wicked Cunning

Every conscious creature has a capacity for mētis intelligence – that cunning intuition that comes forward in the moment of challenging choices. As Detienne and Vernant note in their work on mētis, the Greeks recognized this intelligence in a wide variety of animals, including the owl, octopus, fox, otter, horse, and others. In its creaturely form, mētis navigates survival through its wits, whether as predator or prey, in solitude or families, on and between sea, land, and sky. The Greeks honored the heroes and heroines who imitated and cultivated their own creaturely cunning for its contribution to human virtue, particularly the wisdom of prudence. But what marks the path of natural mētis towards virtue as opposed to vice? The Greeks identified some villains, to be sure, but these very same villains were often rich in mētis intelligence and admired as such. Sisyphus is one such example.

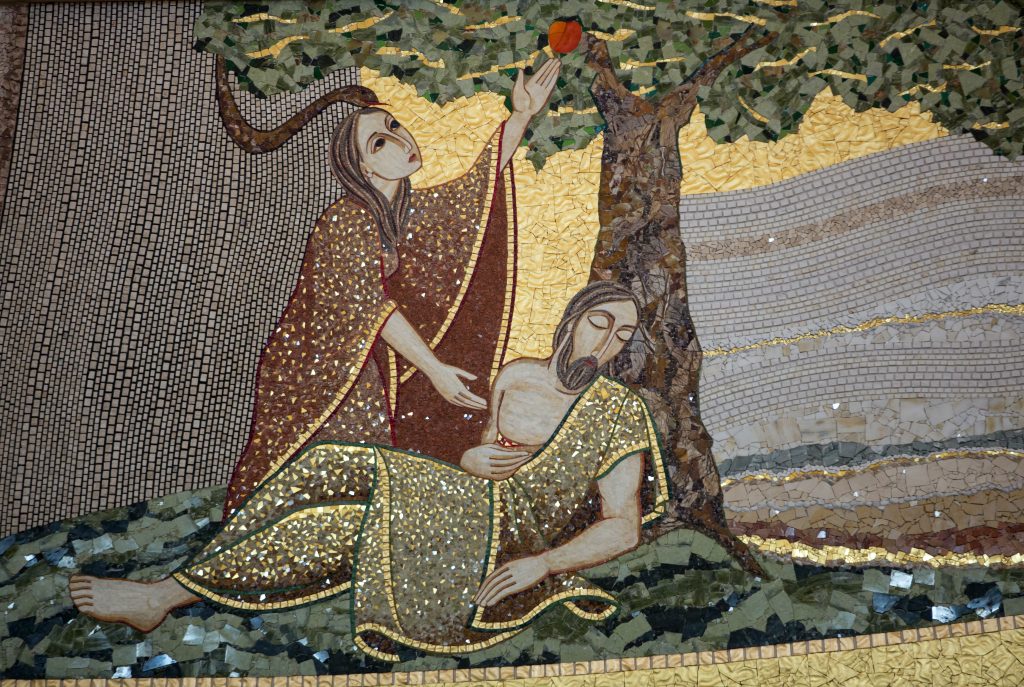

But to appreciate what marks the villainy of cunning Sisyphus in the Western tradition, I propose a counter-example from the East – the Genesis origin story set in the garden of Eden. There is mētis cunning in both the serpent and the woman in this tale, but unlike what we will see in the example of Sisyphus, this woman navigates her path towards wisdom with a sensibility of the high stakes of love and death.

Now the serpent was more cunning than any beast of the field which the LORD God had made. And he said to the woman, Has God indeed said, ‘You shall not eat of every tree of the garden?” And the woman said to the serpent, “We may eat the fruit of the trees of the garden; but of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, God has said, ‘You shall not eat it, nor shall you touch it, lest you die.’ ” Then the serpent said to the woman, “You will not surely die. For God knows that in the day you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree desirable to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate. She also gave to her husband with her, and he ate. (Genesis 3:1-6)

Bringing her attention to this moment rich with potential – the lay of the garden, the pleasing fruit of its trees, and the commandment of the Creator – the serpent uses its own mētis to bring forward the mētis intelligence of Eve to perceive the dimensions of her situation and that she is at the threshold of a liminal crossing. Her next steps, both free and fallible, arise from the cunning navigation of her own possibilities even unto peril. She is in dialogue with the serpent and with herself; she is weighing the process of nourishing body and mind with what is savory and beautiful. She seeks wisdom for herself and for her mate, knowing that it has been associated with death, although death of what kind is uncertain. Death of the body? Death of ignorance? Death of innocence?

Eve navigates danger and the unknown for what she believes will procure new gifts for herself and her mate. Eve is as bold in her mētis as a Greek hero. She leaves the timelessness of life eternal for the cycles of desire, birth and death. And for every mētis-moment she, her partner and children face thereafter, her wisdom gift is the meaningful and sober responsibility of knowing life’s freedoms and loving are inescapably fallible, finite and boundaried by death.

This feminist midrash contrasts with the path of nimble intelligence that deliberately rebuffs life’s weavings of dialogue, love and death in favor of more selfish and short-sighted ends. This is a bent mētis, on a path of wickedness. Detienne and Vernant identify Sisyphus as exemplar, whose artful cunning was highly effective in navigating the puzzles, but always and only for his own malicious ends.

Most fully endowed with mētis – with his artfulness, his gift of the gab, his skill in disguising his promises just as he changes the appearance and colour of the herds which he lures away from his neighbours, Sisyphus, the Death-deceiver, emphasizes the proportion of malice which enters into the intelligence of cunning. (Detienne and Vernant, 189)

Here is his story of unrelenting narcissism: After his brother Salmoneus takes the throne, Sisyphus conspires to bewitch Tyro, the daughter of Salmoneus, with whom he fathers two sons. When Tyro becomes aware that Sisyphus has deceived her for his own vengeance rather than love, she kills the children. Sisyphus has Salmoneus publicly charged and banished for the false charges of incest with his daughter and murder of her sons, then becoming king himself. He persists in using mētis intelligence for his own selfish ends, promising Zeus that he will keep the secret of a nymph’s hiding place, but then exchanging the information with the nymph’s father in exchange for a fresh spring of water to solidify his political power. When Zeus banishes him to Hades in punishment, he cunningly dialogues with Thanatos en route, expressing an appreciative curiosity about the chains of death and coaxing Thanatos into a demonstration. He escapes as soon as Thanatos binds himself to demonstrate the chains’ effectiveness. When Zeus calls for his death once again, Sisyphus presses his wife to shame herself and prove she loves him by throwing his naked body into the public square after he dies. Upon arrival in Hades, he wheedles the gods of the underworld to send him back so that he can properly correct her failure to complete the appropriate burial rituals, after which he stays in the land of the living.

Throughout his story, and at every turn, he dishonors loving-kindness and death, and with narcissistic malice. Where lovers and gods imagine that the pleasing words of Sisyphus arise from some kind of appreciation for them and their interests, they find his ego is the sole motivation for action. Without honor, he cheats a just death twice, determined to live even as he manipulates the bonds of affection. In wicked mētis, there is nothing other than an ego in the moment. But in the story of Eve, we see her natural mētis committing to a wisdom path by weighing in-the-moment what will nourish the body and mind of both she and her mate, trying the fruit with its risk of death on herself before sharing it with her beloved. Mētis wisdom is never simple ego-survival; it holds fast to dialectic possibilities and efforts to navigate the tension: I and Thou, Life and Death, Freedom and Responsibility. In these tensions, mētis intelligence is seized to the service of virtue – it is shaped into wisdom mētis.

The wicked Sisyphus has no interest in such tensions, walking the way of malicious cunning for his own self-centered ends, and is famed for his ending-place. Odysseus finds him in Hades, “in torment, pushing a giant rock with both hands, leaning on it with all his might to shove it up towards a hilltop; when he almost reached the peak, its weight would swerve, and it would roll back down, heedlessly. But he kept straining, pushing, his body drenched in sweat, his head all dusty (The Odyssey, 11:593-599).”

This is his final place – rolling the boulder up the mountain over and over without respite. Albert Camus notes the absurdity of this existence “measured by skyless space and time without depth (The Myth of Sisyphus, 120-121).” The only shelter Camus can imagine for Sisyphus in this horror of alienation is an ersatz dialogue with the rock itself, “the myriad wondering little voices of the earth rise up. . . Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world (123).” Unlike Eve, who exits immortality by drawing upon her mētis for a new horizon of knowing, loving, and dying, Sisyphus flouts wisdom, love, and death repeatedly, and is then denied all of them in a place where life and space, time and death, love and dialogue have no retained or accessible meaning. There is only the silence of his absurd ends. And maybe talking to a rock.

This is his final place – rolling the boulder up the mountain over and over without respite. Albert Camus notes the absurdity of this existence “measured by skyless space and time without depth (The Myth of Sisyphus, 120-121).” The only shelter Camus can imagine for Sisyphus in this horror of alienation is an ersatz dialogue with the rock itself, “the myriad wondering little voices of the earth rise up. . . Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world (123).” Unlike Eve, who exits immortality by drawing upon her mētis for a new horizon of knowing, loving, and dying, Sisyphus flouts wisdom, love, and death repeatedly, and is then denied all of them in a place where life and space, time and death, love and dialogue have no retained or accessible meaning. There is only the silence of his absurd ends. And maybe talking to a rock.

Sisyphus’s cunning is no inspiration to me. Give me Eve’s way, and I will accept my creaturely mētis and its fallibility for the sake of love, death, and the hope of virtue. Of course the wisdom path is perilous in these ways; how could something that matters so much be otherwise? But I wonder: Eve’s fame is for her first courageous steps, not her later ones. What would her mature mētis look like, still holding fast to her wits and intuition as a woman in a new world?

References:

- Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant. Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society. Translated by Janet Lloyd. New Jersey: Humanities Press, 1978.

- Bible, New King James Version

- Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by Emily Wilson. New York: Norton & Company, 2018.

- Albert Camus. The Myth of Sisyphus. Translated by Justin O’Brien. New York: Vintage Books, 1991.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sisyphus, accessed on 12/20/2020

Teacher

An experienced instructor, clinical supervisor and recipient of multiple teaching awards, inviting joy and insight in training and teaching settings.

Coach

A board-certified coach, specializing in executive and professional care for strength-building and creativity at growth edges and in leadership.

Speaker

An authentic and warm public speaker, weaving interdisciplinary insights and humanistic perspectives to support a deepening sense of community.

Demand meaning in the moments of your life.

Chart a navigation course that is clear-eyed and nimble.

Cultivate the habits of perspective, creativity, and curiosity.

Call forth your fiercest capacities for courageous authenticity.

Seek Wisdom.

Janēta Fong Tansey, MD PhD