“The spirit of life never dies. It is the infinite gateway to mysteries within mysteries.”

—Lao Tze, Tao te Ching

To know the masculine and be true to the feminine is to be the waterway of the world.

To be the waterway of the world is to flow with the Great Integrity, always swirling back to the innocence of childhood.

To know yang and to be true to yin is to echo the universe.

To echo the universe is to merge with the Great Integrity, ever returning to the infinite.

To know praise and be true to the lowly is to be a model for the planet.

To be a model for the planet is to express the Great Integrity as the primal simplicity — like an uncarved block.

When the uncarved block goes to the craftsman, it is transformed into something useful.

The wise craftsman cuts as little as necessary because he follows the Great Integrity.

—Tao te Ching

Verse 28, trans. R.A. Dale

“To be the waterway of the world is to flow with the Great Integrity, always swirling back to the innocence of childhood.”

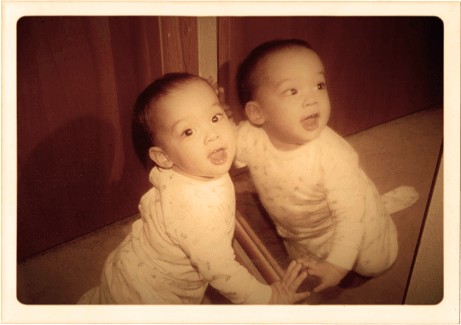

Every origin story contains the seeds of an emerging authenticity. My parents were a courageous marriage of East and West.

Every origin story contains the seeds of an emerging authenticity. My parents were a courageous marriage of East and West.

My father, an immigrant from the urban British-colony of Hong Kong, loved and married my mother, a girl from the Nebraska plains who grew up with wide expanses. Shaped by their respective cultural spaces and spiritual passions, as well as being fiercely independent, they shared a love of knowledge, reasoning, and education. It was no flight of fancy that they chose to give me a Chinese name that means “Pure Thought.”

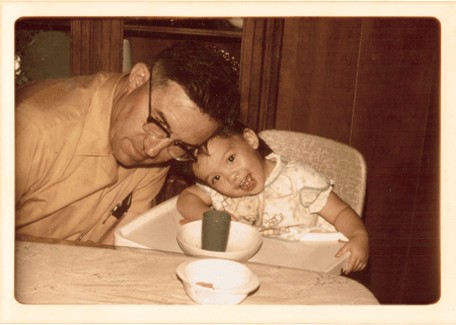

Adored by both my Nebraska and Chinese grandparents, I had a multicultural upbringing from the very start, taught to garden and sew by my mother and to love Chinese cuisine and Monkey King mythology by my father.

The eldest of 8 children, I was fortunate to be raised with a sense of connection, love, and responsibility with a life full of possibilities.

My father’s academic career propelled moves to college communities across the country, from northern Maine to Seattle, and eventually back to Nebraska. With my mother’s love of reading, every move had us boxing up hundreds of books and systematically reshelving them in our new places.

My father’s academic career propelled moves to college communities across the country, from northern Maine to Seattle, and eventually back to Nebraska. With my mother’s love of reading, every move had us boxing up hundreds of books and systematically reshelving them in our new places.

I always had a book in hand, whether nestled at home or in the dusty stacks of the college library waiting for my father to finish his work day. I was fascinated with the stories that explored the edge of what might be possible in the world: mythology, fantasy, biography, and eventually philosophy and theology.

When I decided to pursue a medical career, I knew I could manage Physiology and Pharmacology and the basic sciences, but what I loved was story-telling about the Big Questions. I hoped to find those stories and to hold them in ethical action as a physician.

I was not disappointed; in fact, I was overwhelmed. As a medical student in Chicago, my first clinical experiences occurred at the height of the AIDS epidemic. At that time, AIDS was the number one killer of people my age in the U.S., and it turned the health care system inside-out with questions that challenged old authorities, power structures and dogma.

I was not disappointed; in fact, I was overwhelmed. As a medical student in Chicago, my first clinical experiences occurred at the height of the AIDS epidemic. At that time, AIDS was the number one killer of people my age in the U.S., and it turned the health care system inside-out with questions that challenged old authorities, power structures and dogma.

My patients were incredibly diverse: veterans, homeless, adolescent mothers, immigrants, professionals, working people. As they brought me their stories and needs, the city’s hospitals were full of almost unfathomable suffering and despair, as well as beauty and generosity.

And there were no stories like the ones in Psychiatry, which suited my passion for deep listening, ethics, and mystery. No matter how many of my instructors wanted to insist that neuroscience and standardization of treatment was the future of psychiatric medicine, story-telling was always the yin of heart and spirit that balanced the yang of diagnosis and therapies.

“When the uncarved block goes to the craftsman, it is transformed into something useful.”

I hoped that specializing in Psychiatry would shape me into a useful partner to my patients’ suffering story-telling. But in the 1990’s, the impetus to sub-caption each mental health story with “This is a Broken Brain,” and to restrict inquiry and observations to that which learned-others had categorized and manualized as “evidence-based” was too-often tedious and dehumanizing.

I hoped that specializing in Psychiatry would shape me into a useful partner to my patients’ suffering story-telling. But in the 1990’s, the impetus to sub-caption each mental health story with “This is a Broken Brain,” and to restrict inquiry and observations to that which learned-others had categorized and manualized as “evidence-based” was too-often tedious and dehumanizing.

Senior colleagues were sympathetic, and with their support for a pivot to bioethics, I balanced ongoing clinical work with a re-immersion into Religious Studies, finding my way to the wonder of phenomenology and existentialism.

At the same time, my hospital-based psychiatric practice increasingly turned to the mental health care of patients who were struggling with severe physical co-morbidities like cancer and other life-threatening illnesses, and to palliative medicine. In these healing spaces, existential questions are not armchair philosophy.

“Academia confuses knowledge with knowing.”

“Academia confuses knowledge with knowing.”

So while studies and books fed my curious nature with a generosity of ideas, it was sitting with patients facing sickness-unto-death that called forth the ongoing metamorphosis from head-knowledge to a deeper knowing-together. Who am I? What is the meaning of my life? Or of my death? Why am I suffering? Where is love? And meaning?

But the practice of academic medicine was becoming increasingly standardized, codified, commodified, risk-managed and loaded into electronic databases. I was scheduled into short slots with long lists of patients to be seen and told to leave the humanistic questions to others.

Third-party payers don’t reimburse for much humanism at the bedside. Burnout has been called “an erosion of soul,” and I arrived at that edge.

Academia confuses knowledge with knowing. Most everyone applauds the memorization of the 10,000 trivia.

Beware! These schooled addictions are not just myths — they are a form of mental illness.

Any fragment of the mind, divorced from heart, spirit, human community, and from the primal reality of the universe, is an abomination of the Great Integrity.

Let us prepare for the Great Integrity by cleansing ourselves of all these cobwebs of cluttered fragments that paralyze the mind.

In this way we will function as our own holistic physicians.

—Tao te Ching

Verse 71, trans. R.A. Dale

“Mind, Heart, Spirit, Human Community . . . in this way we will function as our own holistic physicians.”

After completing my Ph.D. in Religious Studies, I exited academic medicine and life as an employee. Designing my own consulting practice was framed as a kind of insurrection at the time, but I can see now that seeking coherence in my own inner and outer spaces has always been part of my story. I wanted to be a holistic physician.

After completing my Ph.D. in Religious Studies, I exited academic medicine and life as an employee. Designing my own consulting practice was framed as a kind of insurrection at the time, but I can see now that seeking coherence in my own inner and outer spaces has always been part of my story. I wanted to be a holistic physician.

And so in pursuit of Integrative Medicine, I trained in energy medicine, meditation, hypnosis, and mindfulness. Wise teachers invited me to spiritually-anchored forms of Tai Chi and Yoga. My religious practices and commitments were supplemented with new voices, new communities, new texts, new sacred rituals.

I celebrated freedom and motherhood, love and beauty: walking in the woods, singing in the choir, raising honeybees. I read hundreds of books, coming back to poetry and mythology, fantasy and biography. I talked with hundreds of people from all different walks of life, with their sufferings, fears, hopes, and infinite possibilities, and at a pace that accommodated dialogue and loving-kindness.

Finding my voice and meaningfulness again, and also in the process of listening to others find theirs, I found joy.

“Mysteries within mysteries, it is the seed of yin, the spark of yang.”

Healing work must be a dialectic of the yang of scholarly knowledge and science with the yin of deeper intuition and heart-centered living. This is but one of many paradoxes in human being and becoming.

Healing work must be a dialectic of the yang of scholarly knowledge and science with the yin of deeper intuition and heart-centered living. This is but one of many paradoxes in human being and becoming.

But life itself is a muse to us, if we pay attention and awaken our conscience. Not because conscience is infallible, but because it is our capacity to discover the shimmering beauty of our own unique lives. Even better when we move from monologue to dialogue and become faces to each other; the stories deepen and love is found.

Join me. You are welcome here.

The spirit of life never dies.

It is the infinite gateway to mysteries within mysteries.

It is the seed of yin, the spark of yang.

Always elusive, endlessly available.

—Tao te Ching

Verse 6, trans. R.A. Dale

Teacher

An experienced instructor, clinical supervisor and recipient of multiple teaching awards, inviting joy and insight in training and teaching settings.

Coach

A board-certified coach, specializing in executive and professional care for strength-building and creativity at growth edges and in leadership.

Speaker

An authentic and warm public speaker, weaving interdisciplinary insights and humanistic perspectives to support a deepening sense of community.

Demand meaning in the moments of your life.

Chart a navigation course that is clear-eyed and nimble.

Cultivate the habits of perspective, creativity, and curiosity.

Call forth your fiercest capacities for courageous authenticity.

Seek Wisdom.

Janēta Fong Tansey, MD PhD